Lst Calls For Deans Resignation And Aba Investigation

Last week we became aware of an ongoing recruiting campaign by Rutgers – Camden School of Law that targets students who were not considering law school. As a part of this campaign, Camille Andrews, Associate Dean of Enrollment, sent students an email with bold statements about the employment outcomes achieved by the class of 2011. When compared to the school's self-published employment data, we see Dean Andrew's statements range from misleading to plainly false. Because the statements made in this email are demonstrably deceptive and are in clear violation of ABA Standard 509, Dean Andrews should resign immediately from her administrative appointment.

There are two important layers to this story. First, Dean Andrews made unfair statements about the employment outcomes of Camden graduates. These statements exaggerate the successful outcomes of Camden graduates and attempt to influence student behavior. The realities of Camden's placement are far different from what Dean Andrews discloses. (More on this below.)

Second, Camden has extended a special offer for people who haven't followed the normal application process and haven't expressed an interest in law school or legal practice. (The email recipients had taken the GMAT, not the LSAT.) The Camden Special allows the students to avoid delay and enroll this August. By portraying Camden as some down-economy safe haven that leads to status and riches, Dean Andrews is attempting to enroll the exact students who ought not to attend law school: people who have not had time to carefully weigh the pros and cons of this significant investment.

In addition to ensuring that Dean Andrews resigns, Camden must also take swift, corrective action in all cases where prospective students received emails containing these or similar false, misleading, or incomplete statements. We also call on the American Bar Association to conduct a full investigation and bring appropriate sanctions against the school for violations of the ABA Standards, especially Standard 509(a) and Interpretation 509-4. Not only is Camden an institute of higher learning, but it also serves as a gateway to the legal profession. The degree of recklessness displayed by Dean Andrews, and the Camden administration for permitting a representative to deceive potential students, cannot be tolerated. It's the latest example of a law school having no accountability for its recruiting practices. These practices must stop.

What follows is an analysis of each unfair statement made by Dean Andrews. We can do this analysis because Camden has made the relevant employment data publicly available, though their accessibility does not excuse false, misleading, and incomplete statements that the administration should know leave readers with incorrect impressions. Each statement is itself a black eye for Rutgers — Camden School of Law, but it's the cumulative effect of all of the statements and all of law school bad behavior that makes resignation, corrective action, and sanctions imperative.

Analysis of Statements by Dean Andrews for Rutgers – Camden School of Law

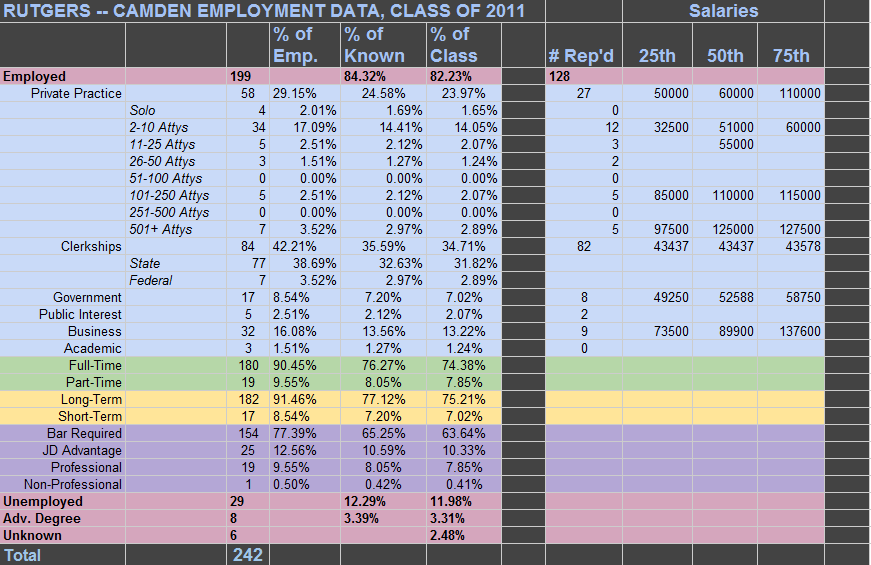

Click image to enlarge. Created from the data Camden provided on its website.

"[O]f those employed nine months after graduation, 90% were employed in the legal field"

This is problematic on two levels. First, it excludes non-employed graduates from the calculation to provide a false sense of success. There were 242 graduates in Camden's 2011 graduating class. Of these, 199 were employed. Camden uses 199 as the denominator with no indication that it has excluded 17.8% of the class from the calculation. While the statement does disclose that it is "of those employed," the number of unemployed graduates is so large that the statement requires context to avoid misrepresenting what it means. The advertised "90% of employed" actually only represents 74% of the whole class.

Second, "in the legal field" implies "as a lawyer," yet Camden groups non-lawyers with lawyers to create the "in the legal field" category. Specifically, Camden has combined two distinct categories: jobs that require bar admission (154 grads) and jobs where the J.D. was an advantage (25 grads). The advertised "90% of employed" actually works out to 63.6% of the class in lawyer jobs, with another 10.6% in jobs where the J.D. was an advantage.

The "J.D. Advantage" category that Camden uses to boost its "in the legal field" rate includes jobs as paralegals, law school admissions officers, and a host of jobs not credibly considered "in the legal field." A graduate falls into this category when the employer sought an individual with a J.D. (and perhaps even required a J.D.), or for which the J.D. provided a demonstrable advantage in obtaining or performing the job, but the job itself does not require bar passage, an active law license, or involve practicing law.

"[O]f those employed nine months after graduation . . . 90% were in full time positions."

This likewise excludes non-employed graduates without indicating that 17.8% of the class has been excluded. Once again, 90% of employed actually means only 74% of the whole class.

"Our average starting salary for a 2011 graduate who enters private practice is in excess of $74,000, with many top students accepting positions with firms paying in excess of $130,000."

There are a number of distinct problems with this statement. First, Camden does not accurately state what the average reflects. The average is "for a 2011 graduate who enters private practice and reported a salary" not "for a 2011 graduate who enters private practice." This is not a trivial distinction. Only 46.6% of graduates in private practice reported a salary. Of those that did so, the numbers were slanted towards higher salaries at large firms. 83.3% of graduates at firms with 101 or more attorneys reported their salaries, while only 37.0% of those at smaller firms reported a salary. The low overall response rate and the bias towards higher salaries being reported mean that the average of responses is not the average "for a 2011 graduate who enters private practice."

Second, Camden does not disclose the salary response rate. The private practice salary response rate (46.6%) indicates that private practice salaries don't tell the whole story. The letter also does not state that only 24% of the class was in private practice. This means the "average starting salary" actually reflects the average salary for just 11.2% of the class. None of this was communicated to the recipients of Dean Andrews' email.

Third, Camden uses the average salary figure without any statistical context. NALP, LST, and many other academics have belabored for many years about how average salaries tend to mislead more than inform. This is because reported salaries fall into a bimodal distribution. For the class of 2010 (across all law schools), there is one peak from $40,000 to $65,000, accounting for nearly half of reported salaries, and another distinct peak at $160,000. This bimodal distribution means that very few graduates make the mean salary of $84,111.

Based on the salary data Camden produces on its website, we see a similar distribution to the national picture across private practice salaries. There were 27 salaries provided; between 8 and 12 were above the $74,000 average by at least 30%; the rest were below the average, with 14 or more at least 20% below the average.

Fourth, Camden claims that many of its top students have accepted positions with firms paying "in excess of $130,000." To be sure, "many" is ambiguous. It might reasonably mean 40% of the class, or even perhaps 20%. With the "top" qualifier, it might not even strain credibility to claim that 10% of the class constitutes "many" top students. Based on the published data, Camden knows that at most five graduates reported a salary of $130,000+, or 2.1% of the entire class. After analyzing the salary data in detail, we think just one graduate did. Whether it is one or five, "many" is far from accurate.

That said, we do know that eight graduates (or 3.3%) made at least $100,000. We also know that Camden grossly exaggerated the salary outcomes of its graduates right after exalting placement success and right before pointing out how its alumni are among the very richest of all lawyers. Of course, this is the same school that reported to U.S. News that its 2011 graduates had an average of only $27,423 in debt, even though the estimated total debt was well into the six figures for a New Jersey resident graduating in 2011 receiving no tuition discount. Fewer than a third (31.7%) of students received tuition discounts, with just 4.3% of students received more than a 50% discount on tuition.

"Rutgers is also ranked high in the nation at placing its students in prestigious federal and state clerkships."

Like Camden, we only have the class of 2010 data to use to compare clerkship placement rankings. With federal clerkships, Camden does okay, tied for 33rd. In terms of percentage of students placed in federal clerkships, it's as close to 16th place as it is to last (188th). Suffice it to say that this exaggeration caps off a legion of false, misleading, and incomplete information used to induce applicants who didn't even take the LSAT.

Other Coverage

- Above the Law (March 18, 2012)

- Professor Paul Campos' Inside the Law School Scam (March 18, 2012)